Diplomacy in the Horn of Africa is rarely straightforward, and Somalia today finds itself walking one of the region’s thinnest tightropes. President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s recent engagement in Nile politics, most notably his attendance at the inauguration of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), has sparked debate over the wisdom and long-term consequences of Somalia’s current foreign policy posture.

The GERD, perched on the Blue Nile in Ethiopia, is more than just a hydroelectric dam; it is a lightning rod of geopolitical tension. For Addis Ababa, the project represents sovereignty, development, and regional influence. For Cairo, however, it is a looming existential threat to the Nile waters on which Egypt’s very survival depends. Most countries in the Horn have been forced to take sides, but Somalia appears to be choosing neither and both.

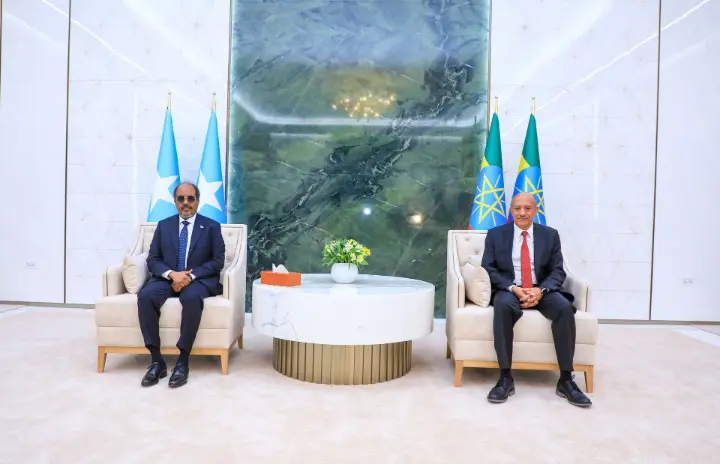

By appearing in Addis Ababa for the GERD celebrations, Hassan Sheikh signalled solidarity with Ethiopia at a moment of national pride. Yet Somalia has simultaneously maintained warm ties with Egypt, a country that has poured resources into supporting Somalia’s security and development agenda. This balancing act, which some observers have dubbed “the diplomacy of facelessness”, is designed to give Mogadishu room to manoeuvre in a deeply divided region.

The logic is understandable. Somalia is emerging from decades of conflict and fragility. It cannot afford to alienate either Ethiopia, its powerful neighbour with outsized influence in regional security, or Egypt, a valuable partner with international clout. Remaining neutral, or at least appearing to, offers short-term survival benefits in a volatile environment.

But neutrality in Nile politics is not a risk-free strategy. The danger is that Somalia’s diplomatic ambiguity could be interpreted as opportunism, eroding trust with both sides. Ethiopia may expect firmer loyalty after gestures like the GERD attendance, while Egypt may question Mogadishu’s reliability if it senses wavering. In a region where alliances are often transactional, credibility is as valuable as geography.

For the Horn of Africa, Somalia’s choices carry broader implications. If Mogadishu can successfully maintain constructive ties with both Addis and Cairo, it could emerge as a quiet mediator, offering dialogue where confrontation dominates. If the balancing act falters, however, Somalia risks being marginalised, pulled into disputes not of its making, and losing the diplomatic capital it is trying to build.

In the end, Somalia’s strategy is a reminder that in African geopolitics, survival often trumps clarity. The question is whether Hassan Sheikh’s faceless diplomacy can evolve into a more defined role, one that not only shields Somalia from regional rivalries but also positions it as a credible player in shaping the Horn’s future.