The Central African Republic (CAR) is once again at the centre of international diplomacy. This week, President Faustin-Archange Touadéra openly defended the presence of around 1,500 Russian mercenaries from the Wagner Group, saying they helped stabilize the country when Western partners were “absent.”

In his remarks, Touadéra highlighted the role Wagner fighters have played in supporting CAR’s army against armed groups that once controlled much of the country. According to him, the Russians provided “timely assistance” at a moment when CAR was isolated, helping secure the capital Bangui and allowing the government to restore some control.

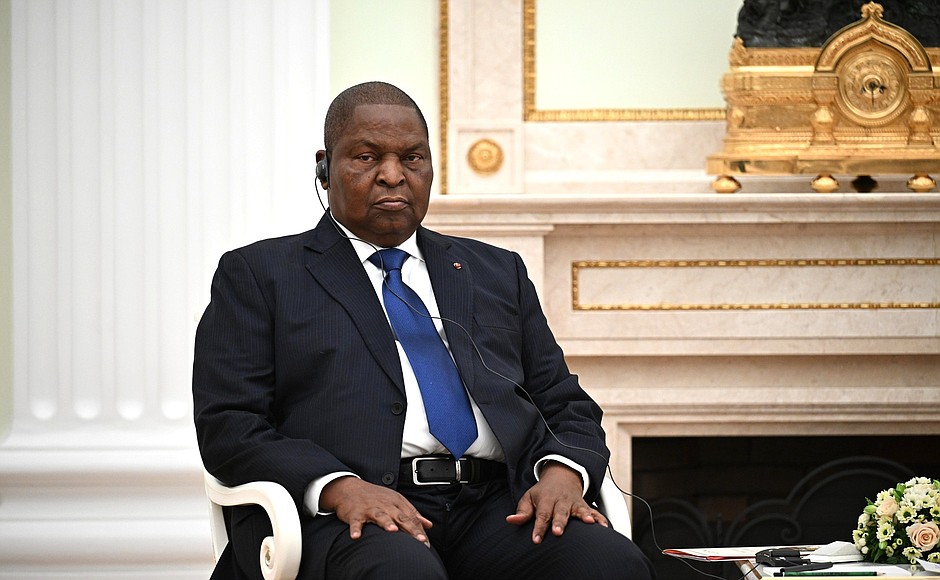

President Faustin-Archange Touadéra

But this defense is not just about security it speaks volumes about Russia’s growing diplomatic influence in Africa.

The CAR leadership is now trying to carefully manage its relationships. On one hand, Russia is its closest security ally, providing military muscle and political backing. On the other hand, Rwanda and Western donor states remain vital for financial support, humanitarian aid, and long-term development.

This balancing act reflects a larger trend across Africa: governments are diversifying their partnerships, no longer relying on one bloc. For CAR, however, the presence of Wagner fighters raises sensitive questions about sovereignty, accountability, and international image.

Russia has been steadily embedding itself across the continent through military cooperation, mining deals, and diplomacy. From Sudan to Mali, and now CAR, Moscow offers governments security assistance without the political strings often tied to Western aid.

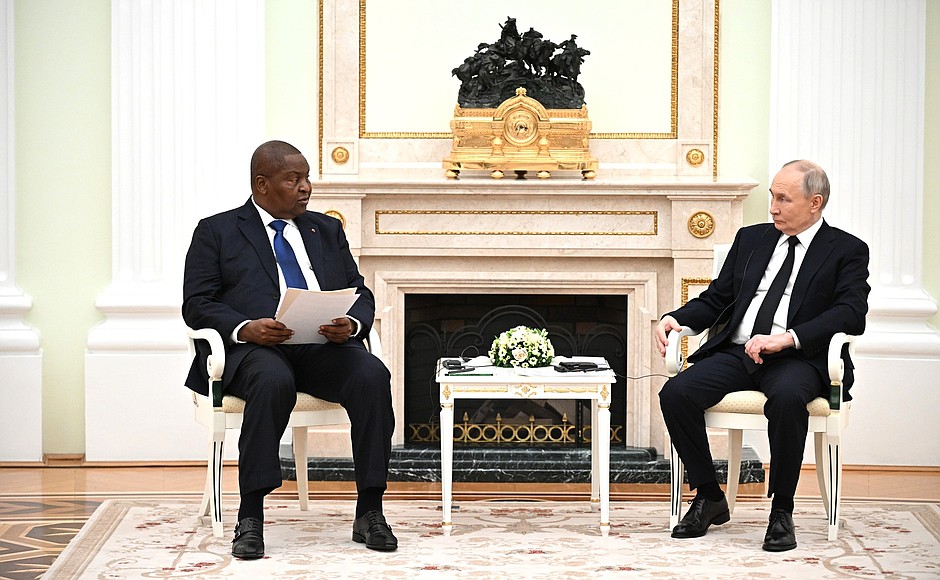

President Faustin-Archange Touadéra and President Vladimir Putin

For struggling states like CAR, this no-strings-attached model is appealing. Yet it comes with costs: Western governments have expressed concern about human rights abuses linked to Wagner, and aid donors may rethink their support if Russia’s role deepens further.

President Touadéra’s bold defense of Wagner is a reminder that CAR is not only fighting insurgents, it is also navigating a high-stakes diplomatic game. Choosing Russia more openly could secure short-term stability but risk alienating Western partners who fund much of the country’s development and humanitarian programs.

At the same time, Russia gains another foothold in Africa’s heartland, showcasing its ability to project power far beyond its borders.

CAR’s defense of Russian mercenaries underlines a shifting global order where African states increasingly play power brokers between East and West. For Touadéra, the gamble is clear: Russia brings security, but the diplomatic costs could reshape CAR’s ties with the rest of the world.

As Africa’s geopolitical weight grows, these choices will matter not just for Bangui, but for the continent’s role in global diplomacy.